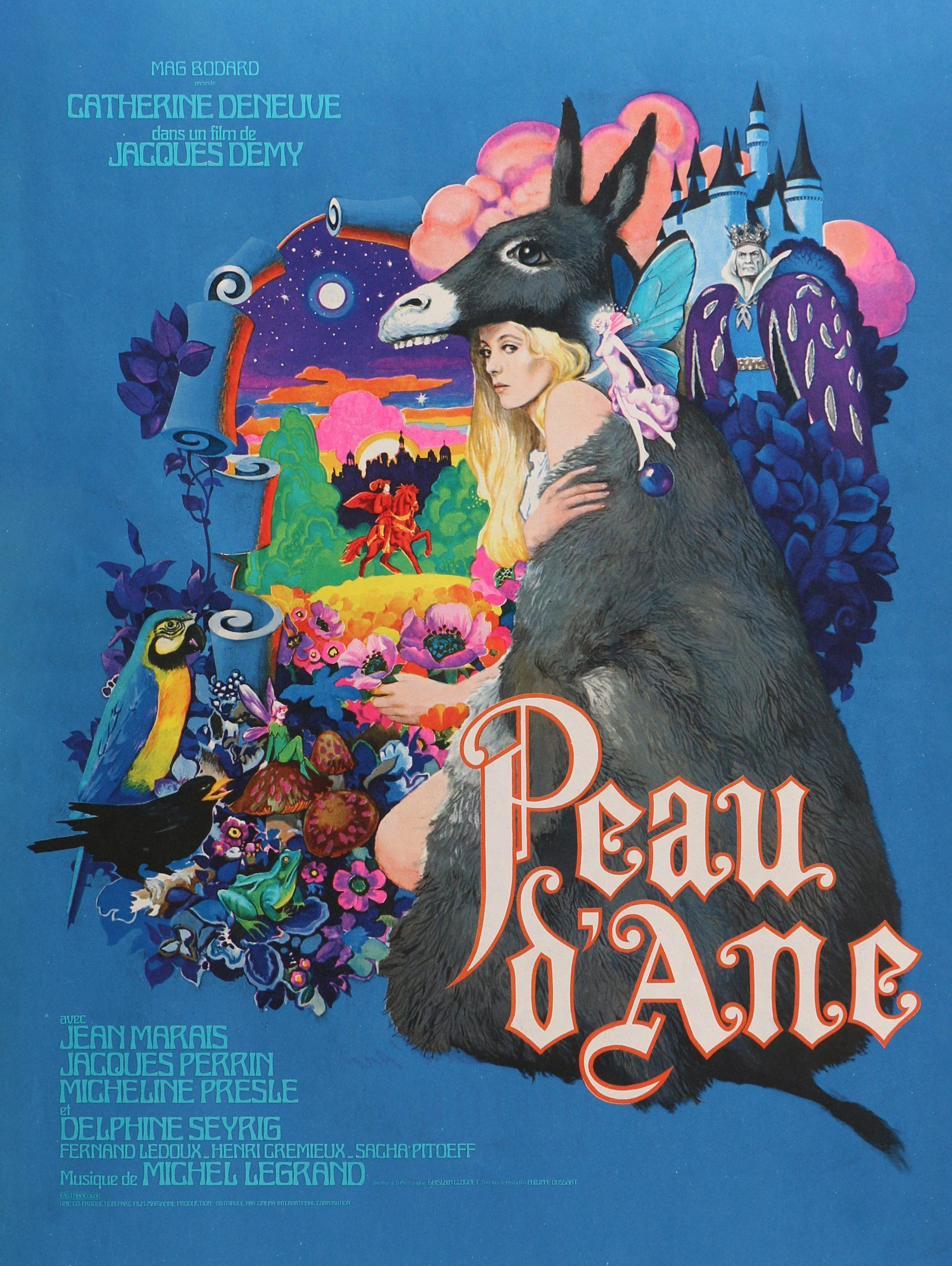

In this lovingly crafted, wildly eccentric adaptation of a classic French fairy tale, a princess must go into hiding as a scullery maid in order to fend off an unwanted marriage proposal—from her own father, the king. A topsy-turvy riches-to-rags fable with songs by Michel Legrand, Peau d’Âne creates a tactile fantasy world that’s perched on the border between the earnest and the satiric. A film by Jacques Demy, starring Catherine Deneuve, Jacques Perrin, Jean Marais, and Delphine Seyrig.

Peau d’Âne

Donkey Skin

Jacques Demy

(1970)

Written and directed by French filmmaker Jacques Demy, Peau d’Âne is a musical fantasy comedy film adaptation of Charles Perrault’s 1694 children’s fairy tale, Peau d’Âne (Donkey Skin), also known in English as “Once Upon a Time / The Magic Donkey.”

Peau d’Âne has also been adapted into other forms, including an opera in 1899 by French composer Raoul Laparra and the first motion picture adaptation in 1908 by French filmmaker Albert Capellani. This beloved French literary fairy tale has been published in France by various publishers in no less than ten editions, not including translations into other languages.

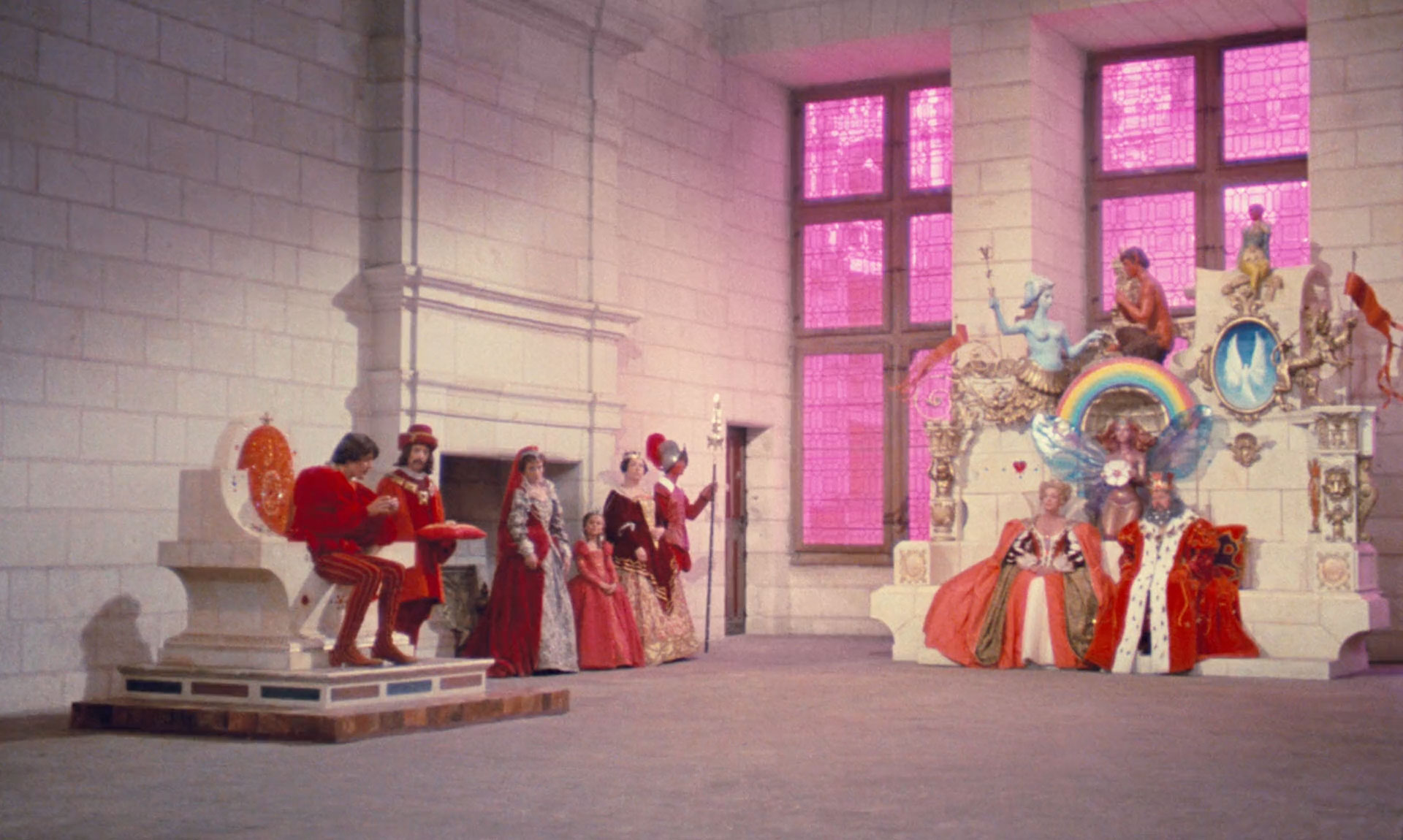

Once upon a time, there reigned a king (Jean Marais), the most powerful ruler in the world. Kind and just in peace, terrifying in war, he earned the fear of his enemies and the contentment of his subjects. His wife, charming and beautiful, was his faithful companion. Their union blessed them with a daughter.

Though their large and magnificent palace buzzed with courtiers, and their stables housed steeds of every size and pedigree, the true marvel lay within the stables themselves. For the place of honor, a position that surprised every newcomer, belonged not to a noble horse but to a donkey with two comically large ears. Yet, this unusual occupant was undeniably worthy of the distinction. Every morning, instead of leaving the usual mess, the donkey deposited a veritable treasure trove: a generous pile of gold and silver coins, sparkling jewels, and even the occasional diamond, gracing its straw. In truth, the donkey was the king’s most beloved and prized possession, its droppings as precious as any jewel in the royal treasury.

The king’s joy, however, came crashing down when his queen was suddenly struck down by illness. He frantically sought help from both revered physicians and cunning charlatans, but none could halt the fever that consumed her day by day. As her final hour approached, the queen, with a voice weakened by pain, implored the king to vow that he would only choose a bride who surpassed her in both wisdom and beauty.

For a time, the king was inconsolable in his grief, both day and night. Several months later, however, his courtiers, fearing that the king wouldn’t be able to produce an heir without remarrying, attempted to introduce him to several selected women. Yet, the king found fault with each one, deeming them less beautiful than his late queen. Finally, one day, a courtier presented the king with a painting of an exquisitely beautiful young woman. Struck by her beauty, the king inquired about her identity. Upon learning it was a portrait of his own daughter, the princess (Catherine Deneuve), the king made a fateful decision: he would marry her.

Driven by a misguided sense of duty and grief, the king proposed marriage to his own daughter, believing it the only way to fulfill a promise made to his late queen. This unthinkable proposal horrified and saddened the princess, who felt trapped by her father’s twisted logic.

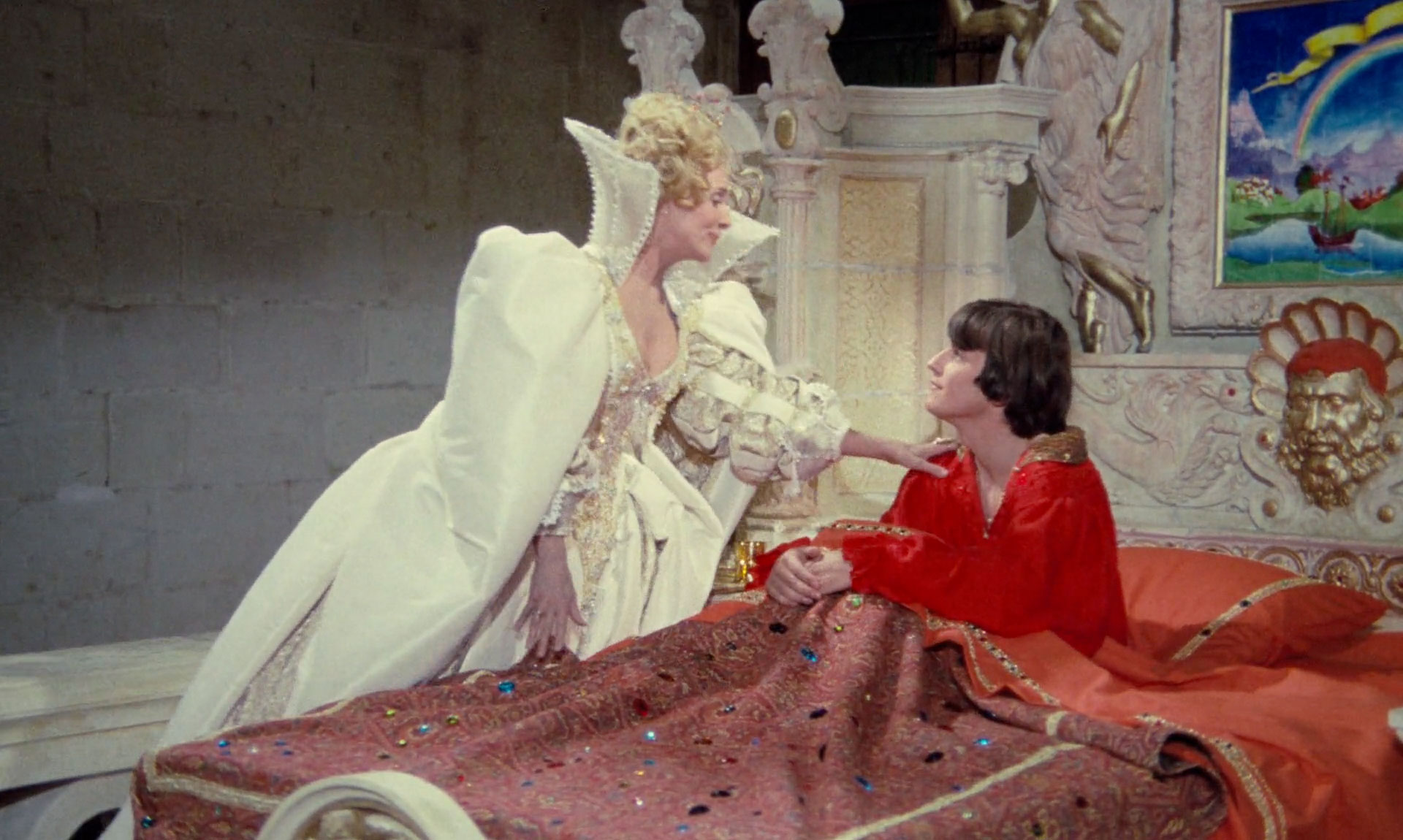

Seeking guidance, she ventured to a grotto adorned with coral and pearls, where her wise fairy godmother resided. Her godmother, La Fée des lilas (Delphine Seyrig), a creature of both elegance and firm morals, strongly disapproved of unions within the same family, citing the potential for unforeseen consequences. In a moment of inspiration, she proposed a clever plan: the princess would request a seemingly impossible task from the king – a dress woven from the very fabric of the sky itself (La robe couleur du Temps).

The king, consumed by his twisted desire, immediately summoned his most skilled weavers and commanded them to create a dress the color of the sky. By the next day, a breathtaking garment of the purest celestial blue lay before the princess. Caught between hope and dread, she knew she had to act. Guided by her wise godmother, she formulated a new plan: she would ask for a dress woven from the very essence of the moon (La robe couleur de Lune).

No sooner had the princess made the request than the king summoned his embroiderers and ordered that a dress the color of the moon be completed by the fourth day. On that very day it was ready and the princess was again delighted with its beauty. But still her godmother urged her once again to make a request of the king, this time for a dress as bright and shining as the sun (La robe couleur du Soleil).

This time the king summoned a wealthy jeweler and ordered him to make a cloth of gold and diamonds, warning him that if he failed he would die. Within a week the jeweler had finished the dress, so beautiful and radiant that it dazzled the eyes of everyone who saw it. At her wit’s end, the princess envisioned no escape from being forced to marry the king. But, in a last-ditch effort, her godmother proposed a peculiar request: the princess should demand the skin of the king’s beloved donkey from the royal stable. Knowing the king’s deep affections for the animal, her godmother hoped to exploit this attachment and force the king to refuse. The princess’ strange request caught the king by surprise. He had showered the donkey with affection and considered it almost a companion. Yet, after a moment’s hesitation, he gave the order to kill the magic donkey, and then he brought the donkey skin to princess’ bedroom while she was sleeping.

The princess awoke in horror to find the donkey skin draped across her bed, a grim reminder of her inevitable fate. Beside her, her fairy godmother materialized, instructing the princess to put on the disguise and slip out of the castle unseen. She also gifted the princess her magical wand, which could summon a magnificent chest brimming with diamonds, clothes, and jewels, ready to appear and vanish at her command.

Early in the morning, the princess vanished, following her fairy godmother’s advice. They scoured houses, roads, and every possible hiding place, but their search yielded nothing. No one could fathom what had become of her. Meanwhile, the princess continued her flight, hands outstretched, begging for work from anyone she encountered. However, her Donkey Skin disguise, so unattractive and repulsive, made her a repulsive creature in everyone’s eyes. No one would offer her refuge or employment. In this guise, the princess eventually found work as a pig keeper in a neighboring kingdom. One day, the prince of this kingdom visited the village. Wandering in the nearby forest, he stumbled upon a hut. Peeking inside, he witnessed her true form – a princess in her radiant beauty. He fell instantly and irrevocably in love.

The prince returned to his father’s palace, his heart heavy with a secret love. He could not bring himself to confess to his parents that he had fallen for a dirty peasant girl living in a hut at the village’s edge. He became withdrawn, sighing and moping, shunning the festivities and losing his appetite. His melancholy deepened, casting a shadow over his days. He yearned to know more about the mysterious maiden in the squalid dwelling. He inquired and was told it was Peau d’Âne, a peasant girl shrouded in an unusual disguise. Some whispered she was a cure for love, a notion the prince vehemently rejected. He refused to forget the beauty he had glimpsed beneath the rough exterior. His mother, the queen, grew concerned by his despondency. She pleaded with him to share his burden, but he could only offer choked sobs and mournful sighs. His only request was for a cake baked by Peau d’Âne’s own hands. The queen promptly dispatched a soldier to fetch the cake.

Peau d’Âne received the soldier’s unexpected order – a cake for the prince himself. With a determined glint in her eyes, she gathered her ingredients: finely ground flour, a pinch of salt, creamy butter, and fresh eggs. Stepping into the privacy of her humble hut, she retrieved her precious recipe book from the depths of her magical chest. Bathed in a soft, magical glow, Peau d’Âne transformed, shedding her rough disguise and revealing the radiant princess beneath. With newfound focus, she followed the recipe for a cake of love (Recette pour un cake d’amour). And, with a touch of magic, she slipped her precious ring into the heart of the batter.

The prince, consumed by his love for the mysterious maiden, devoured the cake with fervent hope. He nearly swallowed the ring when it rolled onto his tongue. He kept the ring under his pillow. Yet, his longing only intensified, his illness worsening with each passing day. The royal physicians, witnessing his decline, reached a grave conclusion: he was lovesick, and only marriage could offer a cure. However, the prince declared he would only wed the woman whose finger bore the ring. This peculiar demand astonished the king and queen, but their son’s ill health left them unwilling to resist. An announcement was made: whoever could wear the ring would become the prince’s bride.

While the plot of Peau d’Âne may seem unusual, it’s surprisingly captivating. I especially love the king’s throne design and the characteristics of La Fée des lilas (Lilac fairy). The complexity of La Fée des lilas is fascinating. She’s neither good nor evil, but rather a nuanced character who offers help while pursuing her own agenda. In the film, La Fée des lilas mentions a poem she gave the king, a poem that speaks of inventions yet to be built in their time.

The music composed by Michel Legrand is exceptional, as always. The color palettes in Jacques Demy’s work are vibrant and fit the story really well. Lead actor Jacques Perrin and lead actress Catherine Deneuve return once again after Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, and give such lovely performances.

Peau d’Âne was theatrically released in France on 20 December 1970. The film proved to be Demy’s biggest success in France, with over two million tickets sold.