A married woman doesn’t feel like she belongs in her husband’s house. A shocking act of violence seems to be the only way out. A film by Veronika Franz & Severin Fiala, starring Anja Plaschg, Maria Hofstätter, David Scheid, Lorenz Tröbinger, Camilla Schielin, Agnes Lampl, Lukas Walcher, and Natalija Baranova.

DES TEUFELS BAD

THE DEVIL’S BATH

Veronika Franz • Severin Fiala

(2024)

In 1750, Upper Austria (Oberösterreich), Christoph (Kajetan Würzinger) tries to soothe a crying baby. However, he’s interrupted by a call back to his house. Forced to leave abruptly, Christoph has no choice but to leave the baby alone in the basket. A mysterious woman seizes the opportunity, snatches the baby, and disappears up the mountain.

Ewa Schikin (Natalija Baranova) walks along the path to the waterfall, holding the baby close. The little one has finally stopped crying. She pauses for a moment, takes off her rosary, and carefully places it around the baby’s neck. As she continues on, the sound of rushing water grows louder. Ewa reaches the top of the falls and stands there quietly, taking in the view of the mountains stretching out in front of her. Just then, the baby starts fussing again. Without hesitation, Ewa lifts the child and lets go, watching as the tiny body disappears over the edge of the waterfall.

Ewa then takes a long walk back to town. She approaches a gigantic establishment, revealed to be a prison tower, and knocks on the door. A person opens the door and lets Ewa inside after she explains that she has committed a crime. We don’t see what really happens to Ewa.

The film cuts to nightfall in the forest, where a mysterious person cuts a finger off a dead woman sitting in a chair. The dead woman appears to have missing toes and fingers, evidently taken earlier by someone else. The person carefully wraps the finger in a piece of cloth. As the person leaves, the camera pans, revealing Ewa’s decapitated head inside a cage next to her body.

Historically, death penalty in 18th century Europe, was carried out by hanging which was the standard method of execution. However, the specific method could vary based on factors like social class, the nature of the crime, and local customs. Decapitation, often by sword or axe, was generally considered more noble form of execution, often reserved for the upper classes or for crimes seen as particularly severe. The use of decapitation in the film isn’t necessarily historically inaccurate, but it may have been chosen for dramatic effect or to emphasize the severity of the crime in the narrative.

Und weil ich vor Verdruß recht müde war dieses Lebens, so kam mir in den Sinn, begehe einen Mord.

Agnes (Anja Plaschg), her mother (Agnes Lampl), and brother (Lukas Walcher) load a cart with wedding dowry and push it through a long stretch of woods to another town for the wedding ceremony of Agnes and Wolf.

After the ceremony, Wolf (David Scheid) takes Agnes to their house on land near his mother’s that he recently bought. Agnes expresses concern about the cost of the house, asserting that she thought they would live in the same house as Wolf’s mother (Maria Hofstätter). Wolf explains that his brother (Stefan Koller) will eventually inherit his mother’s farm, therefore he bought the house with the money he had, plus the dowry and 200 Gulden he borrowed.

Dowries are still practiced in some parts of Europe, though not as widely as in ancient times. They remain deeply ingrained in certain marriage customs and traditions. The dowry serves as compensation to the groom’s family for assuming the financial responsibility of supporting the bride. It helps offset the costs of establishing a new household and providing for the wife. Additionally, the dowry incentivizes the husband to treat his wife well, as he would have to return it if she died shortly after marriage. The size and contents of the dowry, often including clothing, jewelry, and household goods crafted by the bride and her family, signal the social rank and status of the bride’s family.

That evening, wandering through drunken villagers celebrating the afterparty, Agnes sees her inebriated husband, Wolf, blurt out loud to Lenz (Lorenz Tröbinger), his best friend, that Lenz is so handsome while hugging him. Lenz laughs and replies that he likes Wolf too. Agnes doesn’t think anything of it and enters to the house to ask Wolf’s mother Gänglin if she can help with anything. Gänglin tells her that she’s not supposed to do anything on her wedding night. As Agnes’ mother and brother are leaving, her brother gives her a wedding gift, which is revealed to be Ewa’s severed finger.

Later that night, back at Wolf’s house, Agnes kisses the finger and places it under her mattress hoping it will help her conceive a child. However, when Wolf returns, he is unable to perform and falls asleep, leaving Agnes confused about what went wrong. The next morning, Agnes wakes up alone in bed. She wanders around the nearby area, searching for Wolf, where she encounters a woman and two children. Agnes asks them to lead her to Wolf’s pond.

Agnes follows them through the woods. However, Agnes loses them when they suddenly run off and hide. Lost, Agnes wanders deeper into the woods and stumbles across a drawing posted on a tree that shows a woman throwing a child down the waterfall and her subsequent decapitation. On a small hill behind that tree, Agnes discovers an altar with the corpse of Ewa, missing several fingers and toes, sitting upright in a chair. Next to the body, there’s Ewa’s severed head in a cage.

Eventually, Agnes finds her way to the pond where Wolf and Gänglin are fishing with the villagers they hired to help them. Gänglin voices concerns when Agnes doesn’t seem to know what she’s supposed to do, when she prays for far too long, and when she hands two small loaves of bread instead of one to a man who asks.

While preparing dinner for Wolf, Gänglin instructs Agnes to recite ten Pater Nosters, claiming that’s how Wolf likes it. Gänglin seems surprised to learn that Agnes’s family doesn’t pray during cooking. Gänglin also teaches Agnes not to stack skillets because they’ll be scratched, instructing her to hang them on the hooks instead. Agnes becomes frustrated. After Gänglin leaves, Agnes takes the skillets down from the hooks and stacks them back in the same spot.

Pater Noster also known as The Lord’s Prayer is a foundational prayer in Christianity, and it’s likely most people in Austria would have known it by heart, even if they weren’t familiar with Latin.

Agnes becomes obsessed with having a baby of her own. As she spends time at the church, she prays to wax dolls of baby Jesus for a child, befriends a young pregnant woman, and lies down alone in the woods. However, as time goes by, Wolf doesn’t seem to want to have sex with Agnes. Gänglin becomes annoyed by Agnes’s disappearance, especially when she doesn’t show up to prepare food for Wolf. Agnes feels Gänglin is picking on her, criticizing everything she does, gradually driving Agnes into depression.

The next morning, in an attempt to make up for yesterday, Agnes wakes up earlier and makes her way to the pond before everyone else. However, she almost gets stuck in the muddy pond. When Wolf arrives with other villagers, he admonishes her for being reckless to come here alone, asserting that many have drowned themselves in this treacherous mud. Agnes finds a cow skull in the pond, which is considered to bring misfortune.

That night, Wolf’s friend bangs on their door and tells Wolf to follow him quickly, claiming that something has happened to Lenz. Left behind at the house, Agnes hears the sound of a woman screaming in agony. Curious, Agnes grabs a torch and follows the scream, trying to find the source. She only finds herself at a barn where a group of men, including Wolf, are attempting to force open the barn doors. Agnes puts out her torch and watches them in the dark. The barn doors open, revealing that Lenz has hanged himself. Lenz’s mother (Claudia Martini) begs the men to let her bury her son. Wolf is visibly shocked, while the other men load Lenz’s body onto a cart and push it away.

In the 18th century, it was still generally forbidden for the Catholic Church to provide a Christian burial for those who died by suicide. The Council of Trent in the 16th century had reaffirmed the prohibition on funerals for suicides, with some exceptions for those who showed signs of penance before death or were considered insane. Suicide was considered a grave sin against God’s commandment “Thou shalt not kill”. Thomas Aquinas, the influential 13th century theologian, argued that suicide was a sin against the virtues of justice and charity, as well as a crime against God who alone has dominion over life. Since suicide was considered self-murder, the Church taught that it eliminated the possibility of repentance before death, which was required for salvation.

The reason for Lenz’s suicide remains unclear. However, the earlier scene at the party and Wolf’s reaction to finding the body hint at a possible homosexual relationship between them. This would have been considered sinful and socially unacceptable at the time, especially given Wolf’s failure to consummate the marriage.

In 18th century, homosexual acts were generally considered sinful by the Catholic Church and other Christian denominations, continuing a long tradition of religious condemnation. The Catholic Church had long viewed sodomy as a serious sin, with Pope Leo IX labeling homosexuality as “filthy” and an “execrable vice” as far back as the 11th century. By the late Middle Ages, the term “sodomy” had come to encompass various non-procreative sexual acts, including sex between males, and was increasingly viewed as one of the most heinous sins by church authorities. Although it’s important to note that the focus was primarily on homosexual acts rather than homosexuality as an identity or orientation, since those concepts were not yet fully developed. The term “homosexual” itself did not appear until 1892.

At church, the priest gives a sermon to the townspeople, including Agnes. He explains that Lenz can’t be buried because he turned his back on God. The priest says what Lenz did is even worse than murder, so his soul is lost forever. He then mentions that the woman who killed a baby confessed before her execution, so she was forgiven. Later, Agnes overhears Gänglin complaining about her to Wolf. Gänglin says Agnes doesn’t take care of the stable, do chores, or cook for Wolf. She often disappears for hours, shows no respect, and doesn’t listen when she’s told to do something. Gänglin tells Wolf he should’ve married a local girl who could do a day’s work and be a good wife. Hearing all this, Agnes breaks down completely. That’s when she decides she no longer wants to live.

Written and directed by Austrian filmmakers Veronika Franz and Severin Fiala, DES TEUFELS BAD draws inspiration from extensive research into actual court documents and historical cases from 18th-century Austria and Germany. Specifically, the story is based on criminal trial records for Agnes Catherina Schickin from Wuerttemberg, Germany in 1704, and Eva Lizlfellnerin from Puchheim, Austria in 1761-62. The film also incorporates research by historian Kathy Stuart on suicide by proxy in early modern Germany.

Im Europa des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts ermordeten Menschen, die Selbstmord begehen wollten, andere Menschen, um dafür hingerichtet zu werden. Durch die Beichte konnten sie von Sünden gereinigt in den Himmel kommen. So hofften sie, der ewigen Verdammnis zu entgehen, die Selbstmörderinnen drohte.

During the 17th and 18th centuries in Europe, individuals discovered an unsettling loophole in the Church’s doctrine regarding suicide. Suicide was considered a cardinal sin which cannot be forgiven. So, instead of killing themselves, these folks would murder someone else, knowing they would face execution for their crime. They believed that by confessing before their execution, they could cleanse their souls and gain entry into heaven. This macabre practice was not uncommon; over 400 cases have been documented in German-speaking regions alone. Notably, the majority of these murderers were women, and their victims were predominantly children.

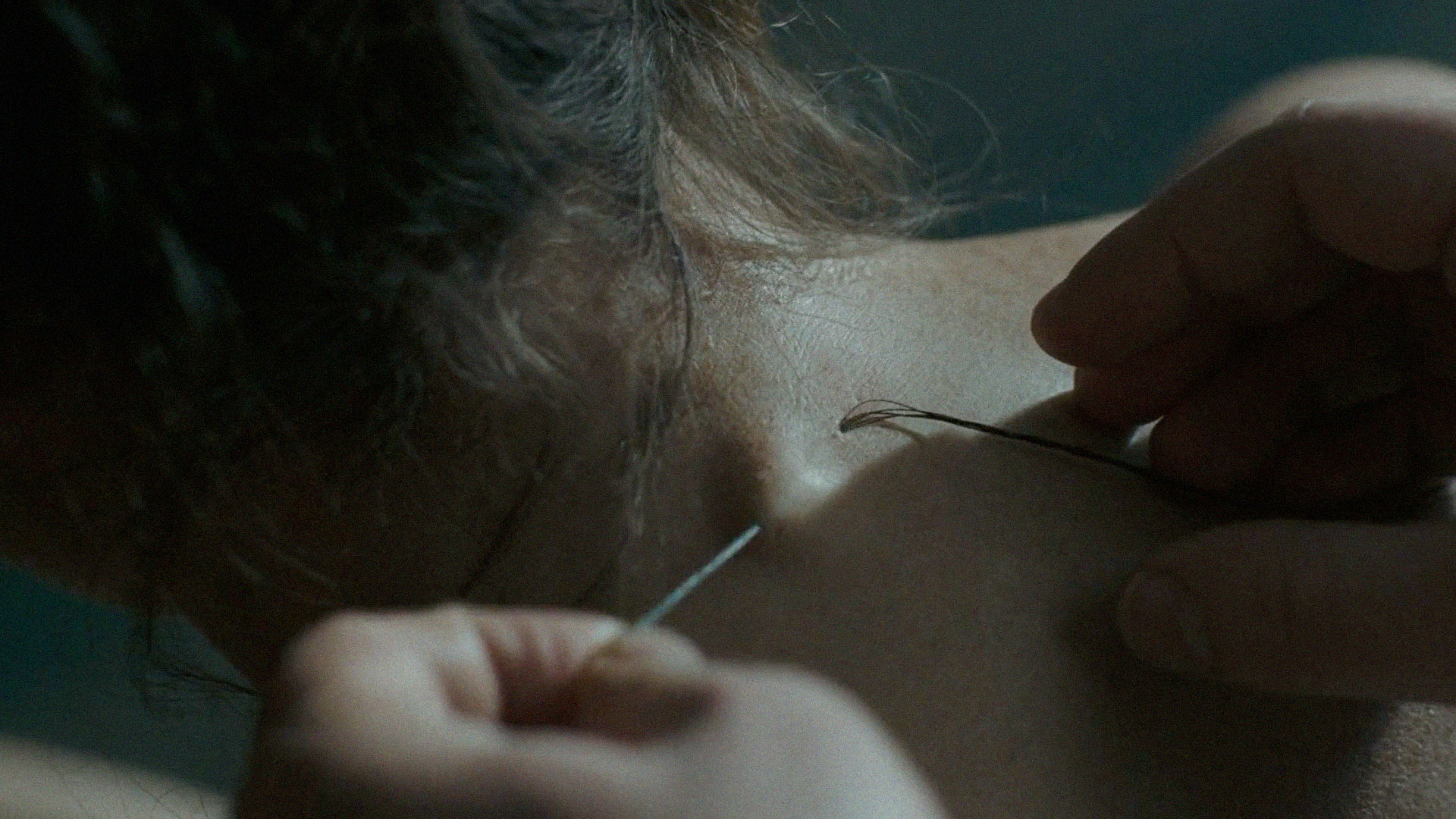

The film unfolds its narrative slowly, almost like a documentary. We quietly observe Agnes experience her life after marrying and moving to another town. However, her life doesn’t turn out as she imagined due to the differences in family backgrounds. The film excels in gritty realism, depicting visceral images of corpses and wounds. A particularly disturbing scene shows the local barber threading a string made from hair through the skin at the back of Agnes’ neck. Several scenes feel exaggerated for dramatic effect, with no further explanation offered. However, this ambiguity also makes them feel unsettlingly real.

DES TEUFELS BAD is a slow-burn film that focuses on the psychological state of its protagonist rather than offering a traditional thriller experience. However, the film suffers from pacing problems. After a shocking opening scene where a baby is thrown down a waterfall, there’s very little that happens for nearly 50 minutes. While the unsettling reality Agnes faces is arguably more terrifying than fiction, watching her mundane life unfold can be tiresome for viewers.

There are also some confusing elements. For example, the film never explicitly explains the reasons behind the protagonist’s mental instability. This makes it difficult for me to emotionally invest in her situation since neither Wolf nor Gänglin are physically abusive to her. Gänglin only wants to teach Agnes to be a proper wife, treating her son as Gänglin believes a wife should. Wolf appears to be protective of Agnes, even excusing Agnes’ erratic behavior with his mother. The film fails to demonstrate what Agnes would want more in life, other than showing that Agnes becomes obsessively wanting a child without explaining why.

In Christianity, “The Devil’s Bath (Des Teufels Bad)” is a metaphorical term used to describe melancholy or deep depression. This concept stems from the belief that severe depression can be a tool or playground for the devil to work in a person’s life. The term suggests that melancholy creates a vulnerable state where Satan can more easily influence a person’s thoughts and actions. In this state, the devil is believed to be capable of: amplifying negative thoughts, making minor issues seem overwhelming, leading individuals to despair, and even twisting small infractions into seemingly unforgivable sins.

A tighter script that removes unnecessary scenes and a shorter runtime could significantly improve the film’s impact. While the ending isn’t entirely unexpected, with Agnes’s fate foreshadowed throughout the film, it effectively plunges us into the horror realm.

DES TEUFELS BAD (THE DEVIL’S BATH) premiered at Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin on 20 February 2024, where it was selected for the Golden Bear (Goldener Bär) in the competition section. The film was also nominated for the Teddy Award for Best Feature Film.

The Golden Bear (Goldener Bär) is the highest prize awarded at the Berlin International Film Festival, also known as the Berlinale. This annual film festival, one of the “Big Three” alongside Cannes and Venice, has been awarding the Golden Bear since 1951. The award is given to the best film in the festival’s main competition section.

DES TEUFELS BAD won Silver Bear for an Outstanding Artistic Contribution (Silbernen Bären in der Kategorie Herausragende künstlerische Leistung). The film was theatrically released in Austria on 8 March.

The Teddy Award, established in 1987 at the Berlin International Film Festival (Berlinale), is a prestigious recognition in the world of cinema, specifically honoring LGBTQ+ themed films. As one of the most important queer film awards globally, it aims to celebrate films and individuals who make significant contributions to queer cinema and promote LGBT+ themes. The award typically recognizes achievements in categories such as Best Feature Film, Best Documentary/Essay Film, and Best Short Film, with an occasional Special Jury Award. Despite being associated with the Berlinale, one of the world’s leading film festivals, the Teddy Award is independently organized.